Aggressive Ovarian Cancer May Be Caused by a Single Gene Mutation

By Jim Stallard, Tuesday, April 1, 2014

This article appeared on the Memorial Sloan Kettering website. Researchers have identified a genetic mutation that appears to cause a rare but very aggressive type of ovarian cancer in young women.

Memorial Sloan Kettering researchers have identified a genetic mutation that appears to cause a rare but very aggressive type of ovarian cancer in young women. The discovery could be an important step toward developing the first effective treatments for the disease, called small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type (SCCOHT). Funded initially by a charitable organization, the research is also an example of the powerful effect philanthropy can have on rare diseases.

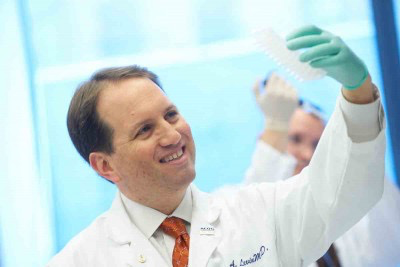

“There are many examples of women in their late teens or early 20s dying quickly from this disease,” says gynecologic oncologist Douglas Levine, who led the research. “The median age at diagnosis is 23, and they usually die within two years — it’s devastating. Finding the cause and a possible target could be a major advance because current therapies have very little effect.”

The discovery was made through the genetic analysis of tumor samples from 12 patients with SCCOHT. Memorial Sloan Kettering genomics researcher Michael Berger sequenced 279 genes that have been implicated in the development or behavior of tumors. This approach, called IMPACT, found that all 12 samples had a mutation in a gene called SMARCA4.

Using human cancer cells, Dr. Levine and colleagues then demonstrated that SMARCA4 plays a functional role in promoting or blocking cancer growth. Inactivating SMARCA4 increased cancer growth, while boosting its expression slowed it down. This buttresses the theory that the SMARCA4 mutation is key to the rare disease.

“I don’t know of many cancers where there’s one gene that is universally mutated and seems to be driving the disease,” Dr. Levine says. “One of our next steps will be to investigate whether this one mutation is actually sufficient to transform any type of ovarian cell into a cancer cell, or whether other factors are involved.”

The finding was reported online March 23 in the journal Nature Genetics.

The Role of Chromatin Remodeling

SMARCA4 helps regulate a biological process called chromatin remodeling. Chromatin is the complex of DNA and protein that packages a cell’s genetic material into chromosomes. The structure of chromatin can be changed (remodeled) to alter how tightly DNA is packaged — which in turn affects how a gene is expressed.

“An increasing number of chromatin remodeling genes are being associated with cancer, and there’s a growing appreciation of chromatin’s role in the disease,” Dr. Levine explains.

The researchers also plan to develop potential therapies and test them on cell lines that carry the SMARCA4 mutation. “Now that we know the target — what we think is the Achilles’ heel — we’ll try to hit it,” Dr. Levine says.

Back to top

Overcoming Research Hurdles

Conducting research on SCCOHT has been exceptionally challenging due to the disease’s rarity. Dr. Levine and his colleagues initially had only three tumor samples from Memorial Sloan Kettering patients. In order to round up enough samples for a more conclusive finding, they contacted a patient group — the Small Cell Ovarian Cancer Foundation — and had a request posted on the group’s website. Slowly, nine more samples trickled in, one from as far away as Spain.

In addition, securing funding to do the genetic analysis on such a rare tumor type was difficult. Dr. Levine credits the critical support of the Katie Oppo Research Fund, an organization founded to increase awareness of and fund research into SCCOHT. Based in Manhasset, New York, on Long Island, the fund was established in honor of Katie Oppo, who died from SCCOHT in 2011 at the age of 19, only eight months after she had been diagnosed.

Katie’s mother, Liz Oppo, leads the organization and was directed to Dr. Levine by a scientist friend of hers who knew she was adamant about funding research into SCCOHT. The fund provided Dr. Levine with initial support to ensure the sequencing could take place. “This philanthropy was key to sending us down this path,” Dr. Levine says. “We never could have made this happen through traditional funding mechanisms.”

Liz says that Katie was about to enter a premedical course of training at Johns Hopkins University when she was diagnosed. Katie was shocked to find that there was very little information available about SCCOHT and vowed that something needed to be done to shed light on the disease.

“I know that had Katie lived she would have done something for this research,” Liz says. “For me, it helps her to be alive. I’m very pleased with the results of this study and know it was not an easy thing to pull off. I’m excited and hopeful we will be able to do more.”

INFORMATION FROM